Frederick Horsman Varley

Frederick Horsman Varley, born January 2, 1881, in Sheffield, England, is commonly known as a founding member of the famed Group of Seven and as one of Canada’s foremost portrait painters. For the last twelve years of his life, Varley lived in Unionville Ontario with Kathleen and Donald McKay. Kathleen nurtured Varley’s later artistic career by setting up a studio for him in the basement of her ancestral home, now the McKay Art Centre located at 197 Main Street Unionville. After Varley’s death in 1969, Kathleen promised to donate her considerable collection of works by Varley and his contemporaries to Markham, to be housed in a gallery suitable for their display and preservation. That promise resulted in the building of the Varley Art Gallery of Markham, which opened in 1997.

Today, our permanent holdings contain close to 600 works by F. H. Varley, including oil and watercolour paintings, drawings, prints, and sketchbooks. Together, these works help illustrate the different types of works Varley created during the course of his career. From portraits to landscapes, the works reveal his evolving style: an individual mixture of solid classical training and of vivid modernist experimentation. Ultimately, they are the product of Varley’s lifelong commitment to art-making.

Discover some of our highlights below.

Image credit: Fred Varley – Saturday, Dec 31, 1960, © Library and Archives Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada.

Ebb Tide, Whitby Harbour, c. 1905–6

Watercolour over graphite on paper

13.0 cm x 21.5 cm

Purchased by the Varley-McKay Art Foundation of Markham, with support from the Elizabeth L. Gordon Art Program of the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation, 2007

2007.5

Frederick Horsman Varley was born on January 2, 1881, in Sheffield, England. He showed a strong interest in the arts from an early age and received his artistic training at the Sheffield School of Art (1892) and at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Antwerp, Belgium (1900–1902). After completing his studies Varley moved to London, where he sought to establish himself as a professional artist. He stayed in the capital intermittently from 1903 to 1908, before settling once again in Yorkshire. Little of his work from this period remains extant, yet the gallery owns four early watercolours created before 1912, when the artist moved to Canada.1

Firmly rooted in the English landscape tradition, Varley enthusiastically embraced the medium of watercolour, as it was perfectly suited for plein-air painting. Easily transported, watercolour enabled the artist to put down on paper his immediate impressions of the natural world. Varley’s early watercolours feature washes of muted colours and speak to his advanced draftsmanship and academic training. An underdrawing of graphite or charcoal would often be sketched out before the application of paint, as is evident in Ebb Tide, Whitby Harbour where a faint black outline peeks through the applied pigment. The details on the foreground buildings, including the sign on the hotel to the right, stand in contrast to the hazy background, where a bridge seemingly disappears in a layer of fog. Touches of blues, greys and whites highlight the boats at anchor and the crowd gathered above. Ebb Tide, Whitby Harbour may have been painted while Varley was an itinerant dockworker, or later when he brought his future wife, Maud Pinder, to the east coast for a weeklong vacation.

1 Rainy Day, London Harbour, c. 1903–5 (2007.8.1); Ebb Tide, Whitby Harbour, c. 1905–6 (2007.5); Yorkshire Landscape, c. 1909 (2008.1.1); The Hillside, c. 1912 (2003.1.1).

The Hillside, c. 1912

Watercolour with traces of charcoal on paper

45.9 cm x 35.0 cm

Purchased by the Varley-McKay Art Foundation of Markham, 2003

2003.1.1

Varley loved the wild, unspoiled hills and moors around Sheffield. He walked and sketched there with his father, with other like-minded artists, and alone. In an interview years later, Varley recalled, “The wilder the country and the wilder the weather, the better I liked it, and often before dawn, climbing the streets of the town before the gas lamps were snuffed out, I would be on the moors to see the stars pale into the day, returning only at nightfall.”1 This countryside served as the inspiration for several of his early sketches and watercolours, including The Hillside. Painted near his village house on the outskirts of Sheffield, this work speaks to Varley’s fascination with gypsies and his interest in the mysterious and fantastical aspects of the woods and its inhabitants. Even as a child, Varley considered gypsies to be a symbol of the free human spirit. Later he would be referred to as the “gypsy” of the Group of Seven, in part due to his wandering soul and mystic nature.

Sinuous tree trunks crown the top third of the painting, while the slope of the forest floor dominates the rest of the work. Although hints of his academic and commercial training still linger, especially in the application of close tonal values of browns and greens, Varley’s brushwork is starting to loosen. Two figures feature prominently in the centre of the work, and the outline of a third is visible in the lower left. The artist’s integration of figures within the landscape reflects the influence of English art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), who encouraged artists to include signs of human presence within their depictions of the land. Varley would continue to populate many of his later works with figures, a trait that would differentiate him from other members of the Group. He brought The Hillside with him when he immigrated to Canada; this watercolour served as the source for the first oil painting Varley painted in Toronto.

1. F. H. Varley, “My Home Town,” transcript of an interview for CBC Radio, July 1939, box-folder 6-4, p. 9., F.H. Varley fonds, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Shelled Buildings, France, 1919

Oil on panel

30.5 x 40.6 cm

Collection of the Varley Art Gallery of Markham. Purchased by the Varley-McKay Art Foundation of Markham, 2009

2009.7.1

From February 1918 to August 1919, Varley was engaged to paint for the Canadian War Memorials Fund, a program established to document Canada’s contribution to the First World War. In a letter to his wife dated October 18, 1918, Varley wrote from the battlefields of France, “You in Canada with all your readings of war … cannot realise at all what war is like—you must see it and live it.”1 Following the advancing Allied forces during the last six weeks of the conflict and standing with them at the front, Varley witnessed untold horrors. As his correspondence attests, Varley experienced more fighting than most war artists did at the time. At the front lines, dodging shells and explosions, he created quick sketches in graphite and watercolour, impressions to be later worked up in the studio. Key works such as For What? and Some Day the People Will Return (both 1918) are now part of the Beaverbrook Collection of War Art at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

After the war, Varley returned to the battlefields of Europe for two months in 1919 to document the devastation left by the fighting. He visited, among other places, Vimy Ridge, Ypres, and Camblain-l’Abbé, as well as Arras, where Shelled Buildings, France was painted. The scene depicts the ruins of the belfry of the Hotel de Ville, which Varley has rendered in broad strokes of brown and greys. The panel also includes such details as figures walking among the ruins and a vehicle in the foreground—signs of life returning to this otherwise barren landscape.

1. F.H. Varley to his wife, Maud, 13 October 1918, Varley Papers, MG-30 D401, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa.

Portrait of Alice Massey, c. 1924–25

Oil on canvas

61.5 x 41.0 cm

Purchased by the Varley-McKay Art Foundation of Markham, 2003

2003.3.1

With the assistance of supportive friends and members of Toronto’s Arts & Letters Club, Varley was able to secure several important portrait commissions in the 1920s. One of the first was of Vincent Massey, scion of the wealthy family whose fortune was built on farm machinery. Following a career in public service, Massey would eventually become the first Canadian-born Governor General of Canada. Satisfied with Varley’s 1920 portrait of him, Massey commissioned Varley to depict his wife, Alice. The work shown here, though a preliminary sketch for the final portrait now in the National Gallery of Canada,1 can be considered complete in its own right.

At the time of execution, Mrs. Massey (1880–1950), née Alice Parkin, was about forty-five years of age. The bust-length portrait depicts her in an unadorned dark dress, silhouetted against a purplish-blue ground. The way her head and neck are shown in strict profile harkens back to depictions of Roman rulers. Her long hair—no flapper bob for the Masseys—is piled up elegantly in a style reminiscent of a Greek goddess and fashionably bound with a wide fillet, or band. The long, swan-like neck keeps her head raised and jawline a perfect horizontal, parallel with the painting’s edge. Completely still and composed while seemingly aware of being on display, Alice Massey is every inch a patrician lady, yet a few small touches—the tendril of hair above her sad grey eye, her cheek suffused with surprisingly fleshy rose pink—give surprising warmth to her countenance and belie the initial froideur.

1. See F. H. Varley, Alice Massey (c. 1924–25), oil on canvas, 82.0 x 61.7 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (no. 15558).

Near Doon, Ontario, c. 1925

Oil on panel

23.2 cm x 33.0 cm

Gift of Leonora D. McCarney, in memory of her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Frank De Rice, 1998

1998.10.1

Void of any evidence of humans, Near Doon, Ontario could be a remote northern landscape, of the type for which the Group of Seven is well known, yet it depicts a long-settled area of southern Ontario. Up close it is a dense weave of paint laid in thick strokes across the surface; from a distance, the image resolves into what at first appears to be a fairly standard composition. In the foreground, a stem of foliage creates a vertical line, which rises on a small mound and then dips down to a middle distance of open ground closed off by an impenetrable background of trees. Varley created more dynamic energy by throwing these three spatial planes slightly off-kilter: the mass of greenery and large tree frame the composition on the right, with the grey rock in the lower left corner. The triangular trees read as conifers, but their brown hue and spots of orange imply deciduous trees beginning to turn in late summer or early fall. The sky is a typical Varley palette of pale turquoise overlaid with lilac. Against these colours, the tips of two fir trees rise antler-like above their fellows and crown the horizon at its centre.

Near Doon, Ontario offers an interesting dating conundrum. It has been attributed to the late 1940s when Varley taught at the Doon School of Fine Arts, in Kitchener. Yet stylistically it fits with his much earlier work. In size, subject, composition and palette Near Doon is very similar to Spring Meadow, Don Valley (n.d.), which Peter Varley, Fred Varley’s son, dates to 1916–18 when the Varley family was living in Thornhill, Ontario. Overall, the paint handling is more similar to works of the late 1910s and 1920s than the 1940s, and a printed label on the back of the work dates it to circa 1925. The signature may offer a clue. Near Doon, Ontario is signed in the lower right corner with “F. H.” above a slightly curved “Varley.” While the way the artist signed his work is not always consistent within a given period, this specific format does appear in several other works from the late 1910s to the early 1920s, reinforcing the possibility that the work is of an earlier date than generally thought.1

1. See Varley’s Gypsy Head (1919), oil on canvas, 61.3 cm x 50.8 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (no. 4836); and his chalk drawing Portrait of Dr. A.D.A. Mason (c. 1923), graphite, charcoal, and chalk on paper, 35.4 cm x 25.2 cm, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, ON.

Snow People, c. 1929

Watercolour on paper

29.0 cm x 36.7 cm

Gift of the Estate of Kathleen Gormley McKay, 1996

1996.1.56

In 1926 Varley accepted an appointment to teach at the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (now Emily Carr University of Art + Design). His move to British Columbia had a great impact on the next ten years of his life, both professionally and personally. While his reputation had rested primarily on his work as a portrait painter, during his first three years in Vancouver he confined himself almost totally to depicting his new surroundings. Varley’s British Columbia landscapes make up an important part of the gallery’s holdings; the gallery houses more than twenty-five works created during either his initial stay in the province or later visits with Kathleen McKay in the 1950s.

On his arrival, Varley was immediately struck by the dramatic landscape of western Canada. He explored the countryside, travelling to Garibaldi Park, Cheakamus Canyon and Lynn Valley, among other locales. He worked outdoors, hiking and camping in the mountains in search of inspiration. This new engagement with the land radically changed Varley’s approach to depicting the landscape. He began to experiment, and the rivers and mountains in his work became more abstract and fluid. He moved away from representing the landscape in its entirety, focusing instead on specific elements, such as a rocky outcrop or mist-covered line of trees.

In Snow People Varley creates a fantastical and mysterious wintry scene. Shades of blue, lilac and jade are applied in an organic manner, creating soft shapes and forms like piles of snow accumulating after a flurry. The scene was very likely painted at Grouse Mountain, which Varley described in a letter as “full of fantastic forms, wind carved & polished, where one can bathe in prismatic colours, incredibly pure.”1 This watercolour painting is closely associated with two other works, a pencil sketch (see below) and an oil painting (private collection), depicting the same scene. In each work, Varley imposes anthropomorphic qualities onto the landscape; the mantle of snow has been made to resemble human forms. These forms are somewhat ambiguous in the watercolour here but are more pronounced in the other two pieces. In the oil painting, a figure was added in the bottom left corner, almost as a witness to this magical transformation.

1. F. H. Varley to Arnold Mason, 15 April 1929 (McMichael Canadian Art Collection archives). Quoted in K. Janet Tenody, “F.H. Varley: Landscapes of the Vancouver Years” (master’s thesis, Queen’s University, 1983).

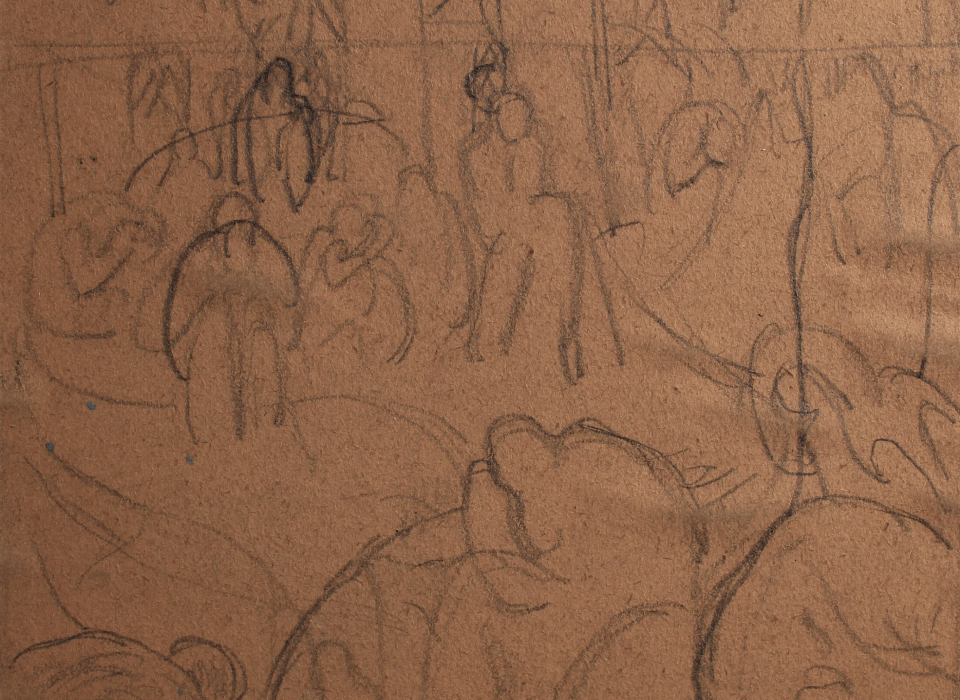

F. H. Varley, Study for Snow People, c. 1929, graphite on paper mounted on card, 17.6 cm x 19.5 cm. Collection of the Varley Art Gallery of Markham, Deaccessioned from the Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Kathleen McKay, 1976, Donated by the Ontario Heritage Foundation, 1988. 2020.04.234

Jericho Beach, c. 1931

Watercolour, graphite, and pastel on paper

22.8 cm x 26.5 cm

Gift of The Estate of Kathleen Gormley McKay, 1996

1996.1.51

Shortly after arriving in Vancouver, Varley and his family settled in a former boathouse overlooking Jericho Beach. These were happy times for the Varleys. The house bustled with energy, the door always open for friends and colleagues to enjoy the beach nearby. A long porch wrapped around the second floor of the dwelling offering panoramic views of the water’s edge. From this elevated vantage point, Varley was inspired to render the evolving atmospheric conditions and the rising mountains across the bay. As his son Peter Varley explains, “There, between sea and sky, we looked out over the perpetually changing water; tides moving over sandbars, cloud forms for every season and subtle shifts in colouration through the long dawn and evening lights.”1

Varley imbues Jericho Beach with warm hues of orange and yellow pigment, suggesting the glow of the setting sun. In this rendering of the bungalow, the seaside dwelling dominates the right half of the drawing, with the second-floor porch echoing the horizon line below. The blue-green of the water and the pale purple of the distant mountains act as a visual counterpoint, allowing the eye to linger before being drawn back to the main focus of the beach. A visible graphite underdrawing provides additional structure and detail to the scene. Figures dot the foreground, standing and climbing up from the beach, while a solitary silhouette watches from the balcony above. Perhaps Varley has placed himself in the drawing as a witness to the scene below, a practice he repeated in many of his British Columbia landscapes.

1. Peter Varley, Frederick H. Varley (Toronto: Key Porter, 1983), 16.

Mountain Road, Lynn Valley, c. 1932–36

Oil on canvas

30.5 cm x 38.0 cm

Gift of the Estate of Kathleen Gormley McKay, 1996

1996.1.87

The most productive period of Varley’s British Columbia sojourn was the time spent at Lynn Valley. The artist moved to the area during the summer of 1934, having discovered it while hiking north of Vancouver two years earlier. The early 1930s proved a difficult time for Varley. Having left the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts over salary disputes, he started his own art college in 1934 only to see it close a year later due to financial difficulties. By this time he was separated from his family and living in near poverty. Varley’s move to Lynn Valley brought him back to nature and provided him with a temporary escape from these hardships. He settled in a house located on top of a hill, offering him a panoramic view of Lynn Peak and Mount Seymour. From the second-floor window, he could see Lynn Creek winding through a deep gorge, straddled by a bridge that marked the way to Rice Lake. With Vera Weatherbie as his companion, he was happy; he painted, played the piano, and lived modestly.

The main focus of this painting is Lynn Peak, which Varley affectionately nicknamed “The Dumpling.” It became one of his favourite subjects, and there exists a large body of drawings, watercolours, and oil paintings depicting this scene. All of these works present a similar view: a road winding around the base of the peak, with a small house nestled there. A series of dead trees, scattered within the landscape, stand tall against the profile of the mountain. Other elements, such as a fence or even a figure walking on the path, could be introduced depending on the medium and the level of detail it allowed. In this rendering, the peak is painted with strokes of deep purple, highlighted by areas of blue and rose. Behind it, Varley has painted a dark foreboding cloud that contrasts with the otherwise bright and luminous scene below.

Mountain Landscape, Lynn Valley, c. 1932–36

Watercolour over traces of charcoal on paper – 28.5 cm x 33.9 cm

Gift of the Estate of Kathleen Gormley McKay, 1996, 1996.1.90

In Mountain Landscape, Lynn Valley Varley renders the topography of Lynn Peak through washes of colour placed both side by side and layered on top of each other. The blues, purples, browns and greens that distinguish rock from tree are similar to the palette used in Mountain Road, Lynn Valley, yet appear more muted and flat in watercolour. Some of the details present in the oil painting are still visible—the dead tree trunks, for example—while others, such as the bridge, have been left out. An increased familiarity with his surroundings enabled Varley to concentrate on the essential elements of the scene before him. The upper part of the sky, as well as the road to the left of the peak, have been painted with a very light wash, allowing the paper beneath the watercolour to remain visible and become an integral component of the work. Varley’s economy of line and composition creates a fleeting sensation: we seem to be viewing an ephemeral landscape, floating on the surface of the paper.

Varley worked in watercolour throughout his career, yet it is in British Columbia that it became essential to his practice. Notwithstanding the importance for Varley of its inexpensiveness and convenience for working outdoors, the artist came to realize that watercolour was the medium best suited to record the landscape and atmosphere of western Canada. As early as 1949 Donald W. Buchanan wrote in Canadian Art magazine: “Varley has in fact excelled and surpasses all other Canadian artists of his generation in his ability to depict the less austere and more mysterious moods of Canadian nature in watercolours of great delicacy, in which he merges acute perception with a high degree of simplification.”1 Watercolour painting also allowed Varley to translate his growing interest in Asian art, specifically the work of Chinese artists from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, to the Canadian landscape. This is particularly evident in his Lynn Valley works as he moves beyond immediate representation to evoke the atmosphere of a scene. He also uses the medium to infuse his work with spiritual meaning. As noted by art historian Joyce Zemans, “The fluid brush work, the planar unity and the integration of elements embody Varley’s pantheistic vision.”2

1. Donald W. Buchanan, “The Paintings and Drawings of F.H. Varley,” Canadian Art 7 no. 1 (October 1949): 3.

2. Joyce Zemans, “Varley: An Appreciation” in Peter Varley, Frederick H. Varley (Toronto: Key Porter, 1983), 67.

Tree (Ferdinand the Bull), 1940

Oil on panel – 24.7 cm x 29.4 cm

Gift of the Estate of Kathleen Gormley McKay, 1996, 1996.1.82

This small oil painting of a large elm tree looming over a pastoral landscape is one of several works painted by Varley in the summer of 1940. At the invitation of Wing Commander C.J. Duncan and his wife, Rae, Varley spent several months at their cottage on the Bay of Quinte near Trenton, Ontario. He developed an affection for the giant elms he observed during his treks in the countryside and painted several works with them as a focal point. Christopher Varley describes his grandfather’s “sparkling and jocular” studies of these majestic trees: “The trees’ top branches rise like plumes, or spin like pinwheels above the surrounding farmland. At times, the earth itself seems to heave, tossing the billowing trees high into the air.”1 In effect, energetic brushstrokes convey a sense of movement and vigour in the scene that is not found in Varley’s other works of this period. The layering of various shades of pinks, purple, greens and blues complements the bright red used to portray ground, tree and sky.

The title of the piece most likely refers to the children’s book The Story of Ferdinand (1936) written by Munro Leaf and illustrated by Robert Lawson. The book tells the story of a young bull, Ferdinand, who would rather lie under a tree than participate in bullfighting, as is expected of him. We don’t know why Varley chose this title for the piece. Perhaps he saw a resemblance between the tree illustrated in the story and the elms in the Trenton countryside. Or, he may have felt a connection to the poor animal, a kindred spirit, misunderstood by those around him. The name also comes up in a letter to friends Len and Billie Pike, where Varley exclaims, “I’ve got tired of my country friends—Ferdinand the Bull and his twenty loves—Humph!!! Inconsistent & Insulting—Damn him.”2

1. Christopher Varley, F. H. Varley: A Centennial Exhibition (Edmonton: Edmonton Art Gallery, 1981), 146.

2. F. H. Varley to Len and Billie Pike, undated (likely early September 1940), Varley Papers, MG-30 D401, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa.

Liberation, 1943

Oil on canvas – 71.2 cm x 61.3 cm

Gift of the Estate of Kathleen Gormley McKay, 1996, 1996.1.86

Liberation is one of Varley’s most intriguing paintings. Depicting the resurrected Christ emerging from his tomb, it is an allegorical composition that speaks to both a spiritual and artistic reawakening. In reference to the painting, the artist explained: “I don’t know yet whether I believe in the Divinity of Christ, so instead of the Resurrection I call it the Liberation.”1 Varley held a keen interest in religion and read widely on the subject. Many of his works, including Dhârâna (c. 1932; Art Gallery of Ontario) are infused with similar spiritual allusions.

Painted while the artist was in Ottawa during the Second World War, in 1943, Liberation is a second, much smaller version of his canvas of the same title painted in 1936, now in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario.2 Despite the vast difference in scale and colour palette, the two paintings are similar in both their execution and composition. Both feature a semi-nude male figure emerging from a rectangular stone archway. In the 1943 painting, the figure stands tall, with one foot over the threshold, facing the viewer with green eyes aglow. His left hand is outstretched, and a beam of light pierces his open palm. This bright yellow-green light emanates from deeper inside the tomb, spilling out into the foreground and illuminating an otherwise dark and foreboding environment. As the art historian Ann Davis has suggested, the figure seems “transformed in front of our very eyes from spirit to man and back again.”3 This ghostly duality, enhanced by the figure’s otherworldly appearance, further emphasizes the painting’s mystical qualities.

Varley painted the original Liberation as a means to raise his artistic profile following his stay in British Columbia. While he was thrilled with the results, the painting was not met with the same degree of enthusiasm by the critics. The second work was also panned by critics and deemed controversial when it was exhibited at the Roberts Gallery in Toronto in 1944. Nonetheless, Varley refused to part with it, and thus it remained with him until he died in 1969.

1. McKenzie Porter, “Varley,” Maclean’s 72/73 (November 7, 1959): 33.

2. F. H. Varley, Liberation, 1936, oil on canvas, 213.7 x 134.3 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift of John B. Ridley, 1977. Donated by the Ontario Heritage Foundation, 1988.L77.131.

3. Ann Davis, The Logic of Ecstasy: Canadian Mystical Painting, 1920–40 (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1992), 35.

Corn Stooks, Doon, c. 1948–49

Oil on board – 30.0 cm x 38.2 cm

Gift of the Estate of Kathleen Gormley McKay, 1996, 1996.1.95

Varley was hired in the summers of 1948 and 1949 to teach at the Doon School of Fine Arts. The school operated from 1948 to 1966 and was situated in the former home of famed local artist Homer Watson (1855–1936), near the banks of the Grand River about halfway between Cambridge and Kitchener in southern Ontario. According to the artist Henri Masson (1907–1966), “Fred had his students all over the fields and spent his days walking around looking for them.”1 The fields clearly offered inspiration for the teacher along with the pupils.

Although known for painting the wilderness in remote northern landscapes, the Group of Seven painted all kinds of terrain, including cityscapes, villages, and farmland. Corn Stooks, Doon falls into the category of pastoral landscape. Five stooks of corn, varying in colour from green to gold, are dotted around the hot, yellow foreground, one poking up from the lower centre of the composition, right against the picture plane—as does the foliage in the foreground of Near Doon, Ontario. This cut-off quality creates a sense of immediacy and places the viewer into the scene. A hill rises behind the cornfield in the middle distance, closing off the view into deep space glimpsed at left. Of similar golden hue, if of deeper value than the cornfield, the hill hems in the space, creating a sense of claustrophobia and thereby intensifying the warmth of a hot, close day. The only relief is evident in the heavens, where malachite-green clouds threaten a cool ultramarine sky.

1. Quoted in Maria Tippett, Stormy Weather: F. H. Varley, A Biography (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1998), 227, 321n76. Her source is a CBC interview with Peter Varley and Henri Masson, 20 May 1969.

Laughing Kathy, c. 1952–53

Oil on board – 38.3 cm x 30.0 cm

Gift of the Estate of Kathleen Gormley McKay, 1996, 1996.1.78

Laughing Kathy, depicting Kathleen McKay, was executed around the same time as the charcoal and pencil drawing Head of Kathy. As with the oil portraits of both Alice Massey and Natalie Kasseb, here Kathy McKay is situated within a shallow, indeterminate space. This work, however, has the greatest sense of movement of the three and certainly the most vivacity. Varley was an admirer of the great British portrait painter Augustus John (1878–1961), famous for his bravura brushwork and ability to capture the personality of his sitters in an imaginative way. Laughing Kathy points to Varley’s awareness of John. Varley succeeds in conveying the impression that Mrs McKay has just this moment turned around, perhaps in answer to her name being called, causing her hair to lift from her forehead and to stream behind her head to the right of the canvas. She is the only one of the three painted subjects to look toward her viewers. The whole image is imbued with spontaneity, as if the sitter did not pose, but was caught on the fly. While there is some stylization—the almost bizarrely long, diagonal neck, the inverted V of the eyebrow—there is an equally strong sense of physicality, of structure, of bones beneath the skin. Mrs. McKay wears a red top, and touches of red are evident across her neck, her face and throughout the background. For Varley the colour red apparently indicated “more terrestrial” spiritual states than the colours blue and green.1 The hue and value of Kathy’s face are similar to those of the background. Her smile, if close-lipped, is warm and wide. She is completely comfortable in her own “terrestrial” sphere.

1. “Varley believed in colour coordinates of spiritual states (blue and green, for example, suggested the highest states of spirituality, red more terrestrial and base ones).” Charles C. Hill, Canadian Painting in the Thirties (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1975), 55.

Outside My Studio Window, c. 1963

Oil with graphite on canvas – 51.0 cm x 61.1 cm

Gift of the Estate of Kathleen Gormley McKay, 1996, 1996.1.80

Outside My Studio Window was completed in Varley’s basement studio in the house he shared with Kathleen and Donald McKay, now the McKay Art Centre, at 197 Main Street in Unionville, Ontario. The Gothic Revival cottage, which the McKays nicknamed “Burdennet,” sits on the Rouge River watershed, and this backyard view frames the property’s lush garden that Varley so admired. While the scenery has changed since Varley painted the work in the early 1960s, many of the trees depicted still grow on the property, including the weeping willow in the foreground. A lean underpainting is visible through an openwork background, upon which small, rapid impasto brushstrokes in Varley’s signature colour palette are applied.

Varley has been described as one of Canada’s most unique colourists. His understanding of colour did not stem from a single source or influence but drew from a combination of his personal insights and the various colour theories he adopted. It was in the late 1920s and 1930s that Varley developed his signature harmonious blends of colour; pale celadon greens, iridescent cobalt violets and bright aureolin yellows became staples in landscapes and portraits alike. As artist Franklin Arbuckle (1909–2001) commented, “Most of his pictures, either figures or landscape, are characterized by a daring use of a breathtaking rose-pink, a rose-pink that simply sings out at you.”1

Varley was in his early eighties when he painted this scene, and it is a good example of the impressionistic style he adopted during the final days of his artistic career. While his enthusiasm for painting never faltered, his sense of observation and skill with the brush naturally diminished over time. This softer, dreamier style can be attributed to advanced old age and deteriorating vision. While attractive, it lacks the confidence of earlier works.

1. McKenzie Porter, “Varley,” Maclean’s 72/73 (November 7, 1959): 33.